Election forecasting is one core occupation of policy analysts all over the world.

Analytic Failure Simulation is a structured analytic technique that can increase the accuracy of estimates. And as a consequence, raise analyst credibility.

Election forecasting can also be great fun. I’ll show you how.

- Overview of the Analytic Failure Simulation Technique.

- Case study 1 – Use of AFAST for Austrian early parliamentary elections forecasting (October 2017)

- Case study 2 – Use of AFAST for Austrian early parliamentary elections forecasting (September 2019)

As you see, I´ve tested this technique on two occasions.

My first-ever attempt at election forecasting was on the occasion of early parliamentary elections in Austria in October 2017. You can imagine my surprise when it came out spot-on. Using AFAST I actually predicted the results for the three top-ranking parties within 1%! Is it amazing or what?

The second tine I used AFAST was to make a preduction about the results of another early parliamentary election in Austria in September 2019. They took place in the aftermath of the (in)famous Ibiza Affair. This time my score was admittedly a tad more modest. But still pretty accurate at least for some key results.

Mind you, I haven’t got any prior experience in election forecasting worth mentioning. I am certainly not a “Superforecaster”, in the parlance of Philip Tetlock. As a matter of fact, I have never taken my ability to produce any kind of estimates with any seriousness at all.

Moreover, I tend to agree with the view expressed by Nassim Nicholas Taleb in “The Black Swan” regarding the general futility of forecasting.

Taleb stipulates that there is no way, and no tool, to overcome the uncertainty inherent in the evolution of real-world issues. Minute random changes in event chains change futures every minute. Future is random, and randomness cannot be predicted. Alternative futures have become so complex and information noise so loud that tracing the most probable path into an even modestly distant future has become as good as impossible.

But what the heck, I still wanted to give it a try.

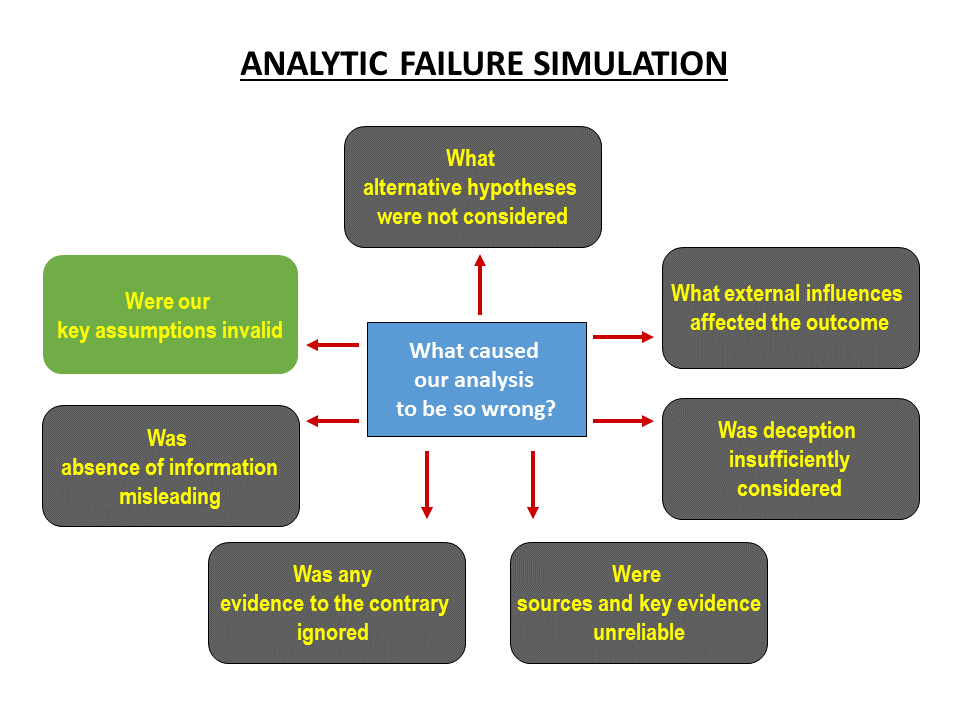

1 . Overview of the Analytic Failure Simulation Technique.

As stipulated by Richards J. Heuer Jr. et al., the technique of Analytic Failure Simulation aims to challenge the accuracy of a conclusion regarding futures analysis.

The starting point: your preferred hypothesis /prediction/recommended action has failed. It is an accomplished fact – now explain why.

The logic of AFAST is quite simple.

The admission of failing in a forecast releases an analyst from the grip of some of his/her most powerful biases. There is no need any more to defend one´s viewpoint, which among other things would have required hiding its flaws.

An analyst can thus discard her/his conclusions and view them clinically from a comfortable distance. Since there wouldn´t be any sense of ownership in them left, an analyst could look at them with a cold eye.

Application of the Analytic Failure Simulation Technique has but one downside.

Well, sort of. It requires time, discipline and mental effort. Precisely because it is a structured analytic technique. Naturally, this is also true for most other SATs.

Come to think of it, it is more of an upside. There is no way it will allow you to cut corners.

Taking Analytic Failure Simulation Technique the full circle involves addressing the following issues.

Here is a short AFAST Checklist:

Here is a short AFAST Checklist:

- Were my key assumption not valid?

- What alternative hypotheses I didn’t consider?

- What external influences affected the outcome?

- Did I not sufficiently consider deception?

- Were some of the sources that produced key evidence unreliable?

- Did I ignore any counterfactual evidence?

- Was I misled by absence of information?

2. Case study 1 – Use of AFAST for Austrian early parliamentary elections forecasting (October 2017)

The ruling leftist Socialist Party and the centrist People’s Party reached the consensus to hold early elections in May 2017. Thus ended several months of political deadlock that all but paralysed government and parliamentary activity.

The junior coalition partner – People’s Party – was fighting for its relevance and political survival. Its role in the government was dwarfed by the all-dominant Socialist Party.

However, the refugee crisis of 2015 several dented the popularity of the quasi institutionalised Socialist Party. Over the span of two years the influx of refugees produced an increase in crime and proliferation of ethnic gangs. Less visibly, it imposed a heavy toll on social security and health insurance schemes. As a result, the right-wing Freedom Party was gaining in popularity by the day.

The People’s Party became acutely aware of a clear and present danger of an imminent collapse of a system set up during four decades of socialist rule. While the socialists might have had some chance of surviving a political tsunami, it could have easily swept the centrists off the board.

In an internal flash coup, both risky and daring, the young Austrian Foreign Minister succeeded in side-lining older-generation politicians in the Popular Party. He then proceeded with reshaping the People’s Party into a vertical hierarchy with himself firmly at the top.

The Austrian public cheered the audacity of the young politician.

Still, my initial forecast came out as follows: 32-28-19.

The Socialist Party will win the election without breaking a sweat with the People’s Party finishing second within 5% and the Freedom Party taking the third place by falling below 20% of the vote.

My initial estimate was backed by the following arguments:

- The belief of Austrian voters in the socialist political establishment has become deeply ingrained in their mind-set and will be very resistant to change.

- Short-term forecast of Austrian economic growth has improved from moderate to record 2,7% (the best in the EU). It is very rare that in times of economic stability and growth voters opt for political change.

- The migrant crisis has subsided. The number of migrants entering Austria has halved, it was expected that only about 8,000 will be granted asylum in 2017 (with the cap set at 34,000). This was a big feather in Socialist´s cap making voters confident in their crisis management skills.

- Supporting soft EU stance on migrants will anchor left-centrist voters. Recent tough speak on border controls and a tougher stance vis-a-vis Turkey on the migrant issue will stop voter drain to the Freedom Party.

- The campaign of the Socialist Party focused on social issues – pensions, minimal pay, lowering taxes. It succeeded in touching the public nerve.

- Vienna is the key to winning the election since it accounts for 18,5% of the national vote. It has remained under firm socialist control for over four decades. The current Chancellor is an ex-top business manager. He will be able to command support from main industrialists and corporations located in Vienna. As a result, Vienna will back the Socialist Party by a solid margin which will become the basis of a nation-wide victory.

- When real power is at stake, nobody has a chance against the “red machine”. Failure is not an option as it would expose skeletons in the cupboard accumulated during decades of socialist rule. Painted into a corner, the Socialist Party will fight like a tiger – and win.

- The candidate of the People’s Party will put up an impressive show. But his rhetoric will deflate when it came to a debate on economic, labour and social issues, in which he had no experience.

Satisfied with the apparent forcefulness of my arguments and key assumptions, I put the subject out of my mind for a couple of days to let the reasoning circuits cool down a bit.

And then I flipped the toggle.

I took it for a fact that the election was won by the People’s Party. And happily grabbed the scalpel. Now, where was my beautiful and now dead initial analysis flawed?

True, Austrian voters were groomed by four decades of socialist rule.

But that is precisely the reason why they would have grown disappointed with the traditional way of doing politics. The bucket overflowed. They wanted a new start. The precedent set by Macron in France showed that that was possible. The People’s Party after a facelift looked like it could achieve it too.

True, the migrant crisis has (temporarily) subsided. But it left a huge mess in its wake.

An explosion in street crime and gang wars had a sickening effect particularly on city voters who used to give stalwart support to socialists.

Several cases of embezzlement of public funds allocated to refugee management came to light, uncovering widespread corrupt practices.

Migrants displayed no intention of integrating themselves into the Austrian way of life. They mostly demanded social security money and to be left alone.

In response, the new People’s Party dynamically repositioned itself by shifting far to the right of the political spectrum.

This move helped to hunt two birds with one stone. It responded to the shift in popular perceptions and expectations. And at the same time it took a bit of wind out of the sails of the Freedom Party. On issues related to border control and migrant management the centrists became “more pious than the Pope”.

True, socialists’ focus on social issues attracted voter attention.

But for the majority of voters, the key election issues were uncontrolled migration and creeping islamisation. There, socialists had little to offer. Besides, both the People’s Party and, above all, the Freedom Party had fairly competitive programmes in this field. They also enjoyed considerably greater credibility among voters.

True, Vienna is a key electoral battleground. But it is only one of the two.

The province of Lower Austria accounts for some 20.1% of the national vote. And historically, it votes People’s Party. Its candidate could win overall if capturing Lower Austria by a wide margin and loosing to the ruling socialist Chancellor in Vienna by a narrow one.

Not an impossible feat. During the electoral campaign the youthful élan and untainted reputation of the centrist Foreign Minister received very warm response from Viennese voters. Particularly, from the younger generation of civil servants and rising stars of corporate business. They saw a sudden chance of taking a shortcut that could save them up to a decade of boring ascent up the career ladder.

True, when painted into the corner, the Socialist Party fought like a tiger.

But that proved to be not enough. The Tal Silberstein affair publicly exposed socialists’ dirty linen, and that looked real ugly.

In a campaign of personalities, the People’s Party candidate was easily everybody’s darling. His political ranking has been consistently high for close to two years. And his new positioning as a moderate rebel for common sense was understandable and appealing to the voters. Last but by no means least, his newly formed political organization was free from scandal or bad news.

The country-wide shift to the right also gave a powerful lift to the Freedom Party.

True, it had to yield some territory to the People’s Party on migration and refugee management issues. But it could still cash in on its biggest asset – credibility among voters.

The whole agenda of the Freedom Party, which it promoted during the better part of the last decade, overnight became political mainstream.

Over the years, its consistent positioning has helped to build up a power base of loyal voters. While the People’s Party could lure away a good chunk of socialist voters, those of the Freedom Party stayed mostly loyal.

The Freedom Party had no ambition of winning. They aimed at taking the second place and getting the role of kingmaker.

Accordingly, my revised estimate of the election outcome was People’s Party 33%, Freedom Party 27% and Socialist Party 25%.

My logic behind the numbers was simple. A winner wouldn´t get more than 35%. A third-place contestant wouldn´t get less than 20%.

If the People’s Party was to win, putting them at 33% will cover both the upper and the lower margin of probable accuracy. There was every reason to expect that they’ll pass the 31% threshold. While a 2% error in an estimate may not be something to boast about, it is nothing to be ashamed about either.

When estimating the result of the Freedom Party, I used a slightly different reasoning to choose the upper boundary in a range of possibilities. While my estimate of the winning result carried minimal risk of being significantly wrong, my estimate of the runner-up performance was realistic but high-risk.

This approach generally follows the strategy for making predictive estimates favoured by Taleb, for whose judgement I have great respect.

Finally, if the socialists ranked only third, it seemed unlikely that they would sink all the way to the 20% bottom. There was still quite some life left in them.

To me, new arguments looked fairly convincing. But in all frankness, so did those underpinning my initial analysis. That is, before I gutted them.

So, my next step was to generate my own data to see which of the two scenarios it would refute.

According to the taxonomy developed by Richards J. Heuer Jr. et al, structured analytic techniques form one of four analytic domains. The other three are unaided expert judgement, qualitative analysis of expert-generated data and quantitative analysis of empirical data.

It is a great idea to use some mix of those. They can mutually enhance each other through feedback loops.

Generating your own data is the next best thing after ice cream.

It can back your conclusions with the solidity data tends to project. And as a consequence, boost both your confidence and credibility. Besides, it can make your estimates more accurate, too. Which should be your ultimate objective, after all. Right?

In my case, it was as easy as one-two-three.

I looked up the results of the Austrian presidential election in December 2016. They were available in minute detail, down to base electoral districts. I was satisfied with using results data for provinces and provincial capitals.

With some sleight of mind I calculated the true voter numbers. Then I made small adjustments to account for new voters and discount for somewhat lower rates of absenteeism that formed part of my estimates.

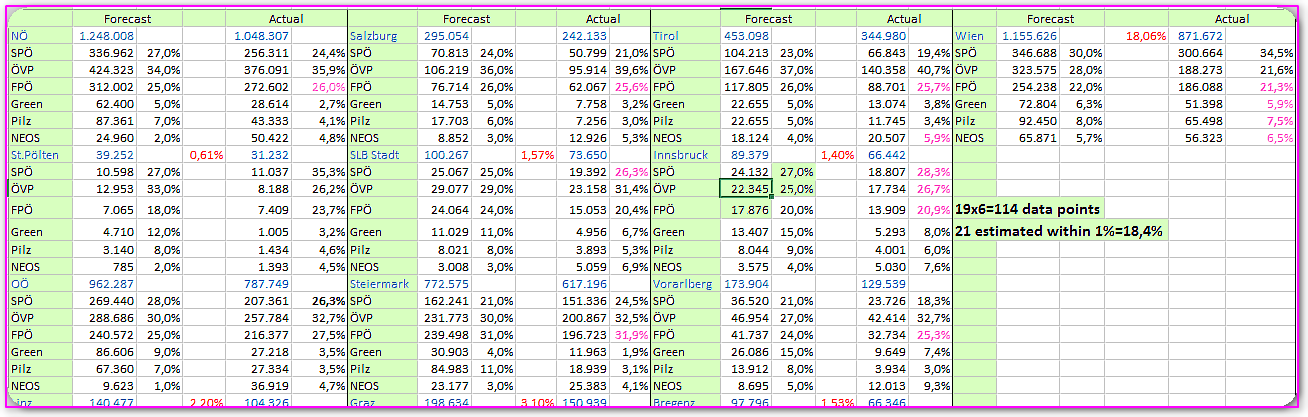

All in all I had 114 data points to fill.

Which I did, taking into consideration various contributing factors. Such as the popularity of socialist Minister of Defence in his native province of Burgenland. Or support from communities in the vicinity of the border with Slovenia to the right-wing proposals of strengthening border control. Or the high level of popularity enjoyed by the candidate from the People’s Party in cities with large universities.

The outcome wasn`t really surprising.

It tended to refute my initial analysis in favour of the estimate achieved through AFAST.

People’s Party – 30,48%; Socialist Party – 26,11%; Freedom Party – 25,70%.

As you can see, this data-supported estimate included a slight twist to my preferred scenario. Simulated data suggested that Socialists would manage to finish second, albeit by the thinnest of margins.

I completed my estimates around 17 August 2017 and forgot all about them. The purity of my experiment shunned recourse to estimate updates.

When the official election results were announced, I was stunned.

My estimate was within 1% for all three top-placed participants and correctly reflected their actual ranking, too.

The final election results were as follows.

People’s Party – 31,47% (my prediction was off by 0,99%); Socialist Party – 26,86% (off by 0,74%); Freedom Party – 25,97% (off by 0,27%).

Did it make me a “Superforcaster”? No, not at all.

It just showed that using the right structured analytic technique did result in a significant improvement in the accuracy of my predictive estimates.

It may be interesting to observe that my fairly accurate forecast was generated by wildly inaccurate data estimates.

Out of 114 data points, my estimates for only 21, or 18,4%, were within 1% deviation from the actual result.

That, however, does not subtract from the validity of the approach involving generation of your own data. Individual estimates may well be way off the mark. Some will inevitably turn out higher and other, lower. But spikes and troughs tend to cancel each other out. And given a sufficiently large number of data points, an aggregate estimate has a good chance of being reasonably close to the true result.

Since then, I had a similar experience with other data sets I generated. As a consequence, I have developed a firm belief in the validity of this method.

For example, it stands up to the challenge when using Force Field Analysis in conjunction with the Futures Wheel technique. Its objective is to suggest the Most Probable Path from a trigger event to one of 16 third-tier futures, which involves generating some 280 data points.

3. Case study 2 – Use of AFAST for Austrian early parliamentary elections forecasting (September 2019)

“Ibiza-gate” led to the meltdown of the coalition government of People´s and Freedom parties formed following the October 2017 election. As you see, despite ending a close third, the Freedom Party effectively did become the kingmaker.

Fast-forward to late August 2019 when I decided to try AFAST once again.

For my initial prediction, I considered the following arguments.

Chancellor Kurz and his government have certainly brought ACTION into Austrian politics.

- A zero-deficit budget plan for 2019.

- A proposal of a comprehensive tax reform.

- Bringing under control migration issues through the adoption of a fairly restrictive Act on the reform of the foreigners´ law.

- Ban on the wearing of hijab in kindergardens and public schools.

- Drastic reduction in the minimum social security payments that made Austria less of an attraction to migrants.

- 60-hour working week.

- Rationalisation of a fragmentated medical- and social insurance system.

As a result, Kurz´s popularity rankings were unprecedented with a 60%+ approval rate. People very much liked his outspoken and result-orientated no-tie approach to governing.

The dissolving of the coalition in the aftermath of “Ibiza-gate” was solely Chancellor´s call. Kurz acted tough and rough and avoided getting hit by the debris.

The Socialist Party failed to mount any kind of sensible opposition to the new coalition government.

For over a year, it remained mired under the rubble of its resounding defeat in the 2017 election. And even after the successor to Ex-Chairman Kern was elected, the party remained on the sidelines.

Appointment of a smart-looking woman as Kern´s successor at first appeared to be a stroke of PR genius. But she just plain failed to leave up to her image and capture the favour of the electorate.

In the 2019 electoral campaign Socialists offered only weak leadership and empty slogans. Plus, lots of ritual chanting about safeguarding workers´ rights and conducting politics with a warm heart and a human feeling.

The Freedom Party, contrary to analysts´expectations, stubbornly refused to be buried by the aftermath of “Ibiza-gate”.

Scandals could scare away only faint-hearted and Freedom Party supporters were anything but. A part of its electorate did walk away in disgust. But the party´s hardcore supporters bit the bullet and closed ranks.

With many of its slogans having been appropriated by Kurz, the Freedom party focused its electoral campaign on the replay of “Homeland comes first” mantra. It sounded a bit stale and hollow but the right wing had no better card up its sleeve.

An early election caused by the sudden and violent demise of the coalition government was bound to become a bonanza for the marginal political movements, particularly the Green Party and the NEOS.

A certain proportion of voters, disillusioned and disgusted by the ugliness and ruthlessness of the methods employed by players in the big-league politics sought refuge in the soft-core programmes broadcast from the side-lines.

The Greens went through a succession of patently irrational chairs. But at long last, found a halfways charismatic and commonsensical leader .

NEOS continued their slow climb, never too bright but never too dumb, either. I suppose they aimed to take the place of the People´s Party of the past in the dead centre of the political spectrum. It remained vacant since the latter´s slide to the right that happened when Kurz took over.

The above assumptions have led me to the below election forecast.

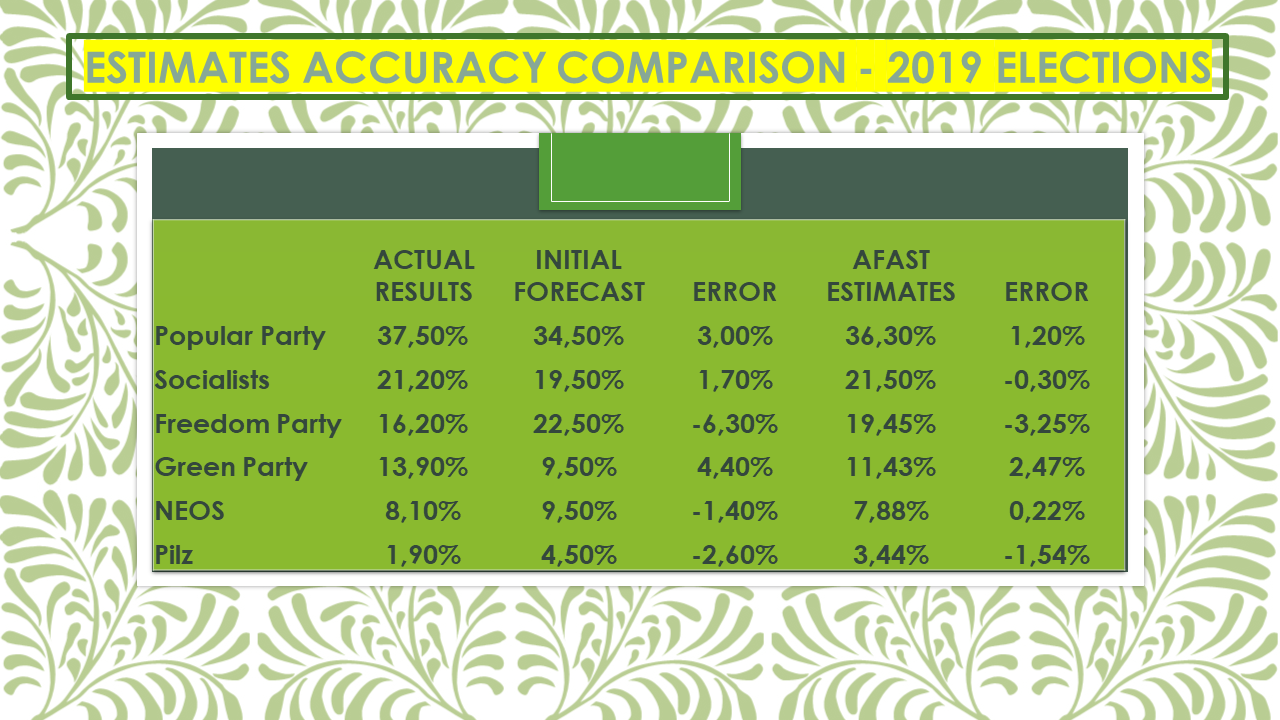

People´s Party 34,5%. Socialist´s 19,5%. Freedom party 22,5%. Green 9,5%. Neo-liberal party (NEOS) 9,5%. Pilz party 4,5%.

Then I flipped the toggle as before and convinced myself that I was dead wrong. While mercilessly slashing through my earlier arguments that I now knew were wrong, I came to the following conclusions.

The real extent of the weakness showed by the Socialist Party in the opinion polls was a bit overestimated. True, their electoral programme lacked substance and sounded hollow. But they still had a healthy-sized following in Vienna and industrial cities. Socialist views could not be wiped out with a single swipe after close to seven decades of mainstream popularity.

For the political right wing, the fallout from “Ibiza-gate” was bound to prove to be more toxic than I ´ve initially considered. Fine, the Freedom Party halfways succeeded in presenting itself a victim of a particularly heinous sting operation orchestrated by some mysteriously occult actors. But getting fooled and acting stupid didn´t earn it lots of Brownie points with its voters, either. Hardcore voters wouldnt´t necessarily defect. But some of them might decide to stay at home rather than go to the polls.

I upped my estimates for the centrist block as a whole. In my reckoning, it included People´s Party, Green Party and NEOS. And looked like product diversification under a single brand. Between them, the three parties offered programmes that catered to every taste between the right-centrist and left-centrist extremes. Such a contsruct was sure to lure disappointed voters from both socialists and right-wingers.

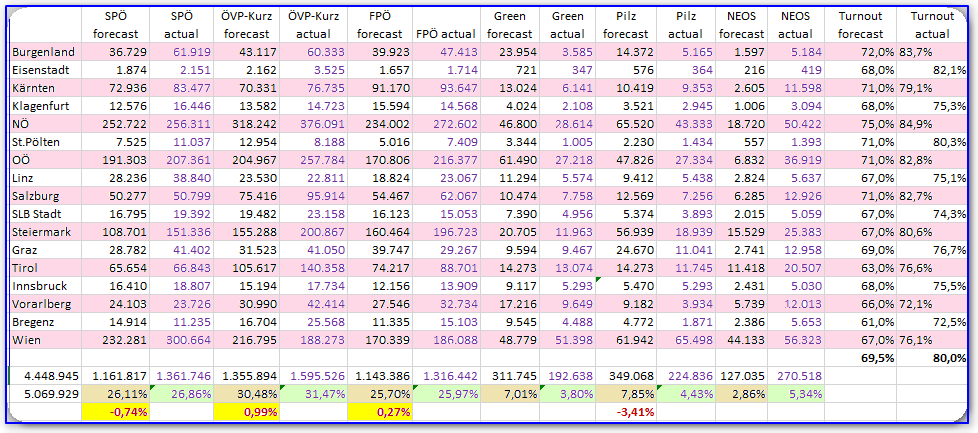

To produce specific estimates, I used the spreadsheets from Case Study 1. The new baseline was the actual results of October 2017 elections.

As you can see, using AFAST I´ve got two results out of six pretty accurately (error under 0,5%). And the other four AFAST estimates were almost twice closer to the mark as compared with the initial forecast.

Still not particularly impressed? I can understand, results of the first case study look more impressive.

But on the whole AFAST did significantly improve on the accuracy of initial estimates this time too. The main reason I didn´t get it real right had nothing to do with the technique. Rather, it had everything to do with my own mindset and its biases. I made some wrong assumptions, that´s all.

- For a start, I assumed that changes in voters´preferences will be of an evolutionary kind. As it turned out, 2019 election took on a terraforming turn and lead to a dramatic reshaping of the Austrian political landscape.

- I also misjudged the extent to which supporters of the Freedom Party would remain unfazed by the fallout from “Ibiza-gate”.

- Finally, I shrugged off the very possibility of an energetic comeback by the Green Party. Only two years before, it got only 3,88% of the vote and was swept out of the Parliament. Considering a forceful rebound never occurred to me.

As a matter of fact, NOONE among Austrian professional election forecasters publicly claimed that their predictions for 2019 elections proved to be correct. So, it was a hard nut to crack.

And here are my final points.

-

If you leave your biases unchecked and make wrong assumptions, AFAST won´t save your day.

-

Structured analytic techniques are no substitute for bias awareness and critical thinking skills.